Providing the smallest of homes is Tokyo's forte; with towers of tiny apartments and minimalist living required, it brings out a certain creativity in the residents. This ability to make the use of the smallest spaces, however, has transferred to the homes themselves, with exceptionally narrow housing growing in popularity, if not in size. Built between existing houses or on narrow strips of land, these homes are as narrow as 1.8 m, making use of the land leftovers that result from the constant subdivision of larger sites. Known as kyoushou juutaku in Japanese, urban gap housing and even eel's nests, the names are almost as creative as the buildings themselves.

Row House (Azuma House), Sumiyoshi, Osaka, in Japan, 1976. Oiuysdfg via Wikipedia used under a CC license

One of the trendsetters of the style was Tadao Ando's Row House, which was only 3 m wide and was completed in 1973. Built in Osaka, it has no exterior windows as the owner wished to feel as if he were not in Japan. An interior courtyard with walkways was included to allow light to enter, displaying the alternative thinking required when faced with both limited space and unusual requests. The issue of windows and limited light is frequent in the world of urban gap housing, as often they are sandwiched between buildings, with very limited options for natural light. While some may go for full transparency on the facade ends like architectural firm YUUA on their 1.8 m house in Tokyo, some clients prefer more privacy.

Internally, the space requires more thought than a traditional home, as light must be maximised and flow maintained. Opting for open-concept over divided rooms and separating sections by floor increases the sense of flow. Mezzanine levels are a common feature in narrow houses, expanding upwards instead of outwards to create the illusion of space. For houses with glass fronts, rooms such as bathrooms and bedrooms are placed towards the back to retain privacy.

However, these homes are not only limited to Japan, with examples cropping up in London, Los Angeles and elsewhere, as people limited by space or finances opt to maximise what they have. The level of minimalist living, however, may mean that this kind of property is more suited to Japanese homeowners. Due to the confines of modern city apartments, combined-purpose rooms are considered standard, while elsewhere, people may find the change more difficult. The traditional fluidity of Japanese rooms enhances this, as minimal furniture and storage space means rooms can often change from bedrooms to living spaces on a daily basis, without a second thought. For countries where fixed beds and sofas are a staple, this fluidity may come as more of a struggle.

Image Credit: 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia

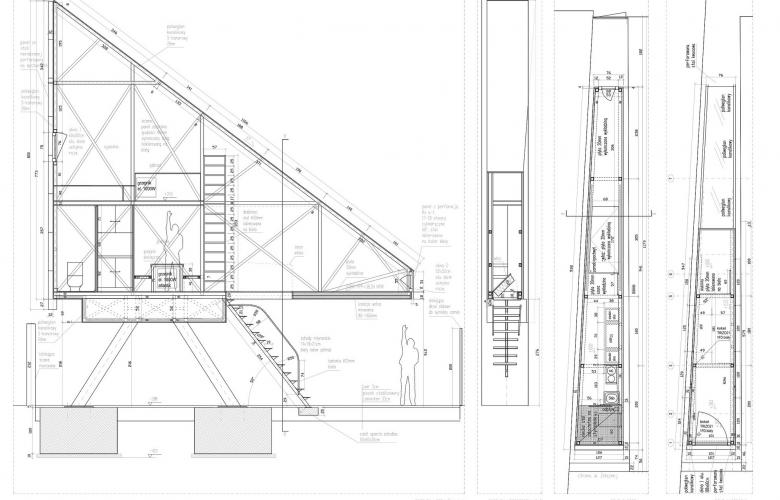

While minimal space has been the limit for most of the designs, it became the goal for one architect in Poland who attempted to build the world's narrowest house in Warsaw. In a tiny space between two buildings, Keret House is 122 cm at its widest point and serves as a writer's retreat. Designed as a triangle, the exterior uses perforated holes to provide light and maintain privacy, with traditional windows at the back. Part art installation, part retreat and part experiment, the house was only intended to be in place for two years but has become a tourist attraction already and the plans are featured in the permanent collection at the MoMA in New York.

While it may not attract everyone, the narrow lifestyle may also become a more permanent feature in our lives as cities continue to grow, and space is utilised beyond expectation.

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

This article was previoulsy published on REThink Tokyo

Articles similar to this on REThink Tokyo:

Weird and wonderful: Japan's unconventional houses

Making a house a (typical) home in Japan

Tokyo gets creative with Airbnb